- Home

- Christopher Hacker

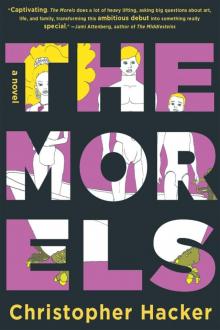

The Morels

The Morels Read online

Copyright © 2013 by Christopher Hacker

All rights reserved.

Published by

Soho Press, Inc.

853 Broadway

New York, NY 10003

This book is a work of fiction. References to real people, events, establishments, organizations, or locales are intended only to provide a sense of authenticity, and are used ficticiously. All other characters, and all incidents and dialogue, are drawn from the author’s imagination and are not to be construed as real.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hacker, Christopher, 1972–

The Morels / Christopher Hacker.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-1-61695-244-0

1. Families—New York (State)—New York—Fiction. 2. Influence

(Literary, artistic, etc.)—Fiction. 3. Family secrets—Fiction. 4. Domestic

fiction. 5. Psychological fiction. I. Title.

PS3608.A248M67 2013

813′6–dc23 2012036639

Interior design by Janine Agro, Soho Press, Inc.

v3.1

For Joanna, and for Mom: Every writer should be so lucky.

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

1. Arthouse

2. Applause

3. Blackout

4. Viktoria

5. Novel

6. Thanksgiving

7. Ending

8. Penelope

9. Rushdie

10. Memory

11. Warhol

12. Collective

13. Suspect

14. Reunion

15. Benji

16. Cadenza

17. Fists

Acknowledgments

1

ARTHOUSE

THE EDITOR I WAS TO fire worked out of his one bedroom in Herald Square. He’d been the lowest bidder on our project by far, his single stipulation that we meet him no more than once a week and he be allowed the other six to work undisturbed, a stipulation we’d had to accept—he was the only editor we could afford—until an old classmate of the director’s volunteered to cut the film for free. The director told me about it that morning over eggs and coffee at the Galaxy Diner. The inconvenience of starting over, he explained, would be minor compared with the inconvenience of filing for Chapter 11.

It was 1999. The last Checker cab in the city had just been retired. All over, people were stockpiling canned peas, just in case. I was seven years out of college, lived at home with my mother, worked for free by day, and by night swept stray popcorn and condom wrappers from the back rows of the arthouse on Houston.

One always got the sense upon entering the editor’s apartment that he was being caught unawares. He answered the door in thick glasses, pillowcase imprint on his cheek. He had a bachelor’s tendency toward strewn clothing and empty beer bottles. It was clear he slept in the living room: gathering the bedding from the sofa like a doghoused husband, he’d make a spot for us while he went about his morning ablutions—and we, waiting with our coffee and script notes, were privy to each splash and fart and groan—emerging with Coke bottles shed for bloodshot contacts, ready, as he put it, for business. The bedroom was where the “baby” slept. The windows went magically dim whenever the sun appeared, giving the place with its blinking lights the cool phosphorescence of a command center. A rack of industrial-strength video recorders stood in a corner. Three monitors displayed the frozen grimaces of our actors, time-code numbers in letterboxed margins. The room was decked out in charcoal acoustic tiling, and against the far wall was an opulent leather couch—to impress the clients, he’d said on our first meeting as we sat smoothing our hands across it. Glass coffee table. Brushed-steel coasters. The editor came in and took up the cockpit chair in front of the monitors. The director opened his binder, and they set to work.

It was a white-trash retelling of Hamlet. A young man returns to his trailer park from a stint at reform school to find his junkyard-king father murdered and his widowed mother shacked up with his uncle, the tractor salesman. The dialogue was funny and hillbilly absurd and conjured a vivid world that by sheer force of will seemed already to exist. The writer-director was a recent NYU grad from Sri Lanka. His father, a Sinhalese tobacco magnate, was reputedly the third-richest man in South Asia. The movie we were making was his graduation present.

Editing seemed mostly about fixing the many blunders of production: underexposed footage lightened, boom mics cropped, flubbed lines trimmed. The problem of the day involved a Winnebago crash, which appeared in these monitors about as perilous as the backcountry amblings of a retiree couple. Something to do with poor camera placement. The editor tried speeding up the footage. I normally enjoyed our weekly sessions here. The couch was like the backseat of a chauffeured Bentley; I took careless pleasure being the passenger on this three-hour journey, allowing the two of them up front to bicker over outframes and cutaways. But today was a carsick three hours. Their bickering, usually playful, had turned ugly. “Decreasing the frame rate won’t work,” the director said.

“It looks better.”

“It looks slapstick.”

“Well, I can’t cut what I don’t have.”

“The word you’re looking for is talent.”

This was my cue. “Let’s take a break,” I suggested. “Get some lunch, talk things over.”

I should have been straightforward. I should have sat him down before he’d even gone into the bathroom to put in his contacts. But I had never fired anyone. How was this supposed to go? While we waited at the fourteenth-floor elevators, arms folded, mingling with our brass reflections, I tried to think of a good segue. And speaking of awkward silences. The panel indicated that the left bank was stopped on three and the right bank was on its way down, pausing at each and every floor along the way. Some homeschooled brat, probably, pressing all the buttons before jumping off.

There was an open door at the end of the hall. Someone was walking back and forth inside an apartment. A brass luggage cart was parked outside, hung with fresh dry cleaning. At a certain point the person (I could see now that it was a man) took the clothes off the hanger and disappeared back inside, then came back out and wheeled the cart in our direction. “Sorry,” he said. “I’d use the service elevator, but the gentleman with the key doesn’t work on weekdays.”

He thumbed the DOWN button—already lit—then turned to puzzle me over for a moment before testing out my name, like a question. He reached out and gave me his hand, which was firm and damp, and I shook it, trying not to let it show that I had absolutely no idea who he was.

This is a problem, one I’ve had as long as I can remember, and often gets me into trouble. In eighth-grade shop class I lost the tip of my left index finger to the jigsaw, and it was only as I was leaving that the teacher discovered the stains coming through my front pocket and the tissue soaked in blood. At precisely the moments I should be calling for assistance (I’m sorry, how do I know you?), I freeze up and am forced to fake my way through. He said his name, but I didn’t catch it. I nodded. “Been a while.”

“Fourteen years,” he said. I asked him what he was up to, only half listening to his answer because I was suddenly aware that I had not introduced my colleagues. He said something about being out in the wilds of Queens since I’d seen him last and that he was now a husband and, if I could believe it—he could hardly believe it himself sometimes—a father. Fourteen years? I tried counting backward. Certainly it put him out of college range. High school?

He was a head taller than me, at least, and I’m not short. He wasn’t handsome: eyes sunken, ears jutting out like pouted lips, brows joined. The backs of his hands were covered with hair. H

e was a hairy man. I could see this in the rash on his neck; it was skin that needed frequent shaving. The only place hair was not persisting, it seemed, was along his receding hairline. It was a face that hadn’t reached its ideal age yet, I thought, like seeing a grandparent in an old Super 8 and finding the familiar face strange in its youth, improbable. And like someone a generation or two older, he had a gravity about him. He was tall without managing to stoop. Though his nose was large, it gave his face dignity. He had on chinos and a windbreaker, loafers with white socks. It was the outfit of someone who was stumped by words like phat and fo’ shizzle and who, if you took him out to a bar, would complain the music was too loud, and couldn’t we just go someplace where we could all sit down? None of this, to say the least, rang a bell.

I turned to Sri Lanka and the editor now, but they had been done with this conversation before it began, striking up their argument again as if this man standing before me were invisible; and indeed to them he was. The movie business is an exclusive club, and to us insiders the rest of you are pitiable wastes of our time. If you were to say that we’re all just arrogant pricks, that you hate the movies and wouldn’t want anything to do with the business of it, what we hear is: I’m jealous. Just observe the way we move into your quiet neighborhood with our cube trucks and honey-wagons, like the Holy Roman Army, even the lowliest of us with our headsets barking orders at you to cross the street: Don’t you see we’re filming here?

The man had pulled out his wallet, apologizing he didn’t have a more recent picture (“Boxed up,” he explained) and was showing me a snapshot that had obviously been cropped with scissors to fit in the little plastic photo sleeve. It showed a dark-haired green-eyed beauty holding a child—a boy, if the blue overalls were any indication—old enough to be sitting up and young enough to be held neatly in his mother’s lap and for the mother to have her chin on his head. The photo sleeve was worn almost opaque, and pocket debris had been stuck inside long enough to have formed bumps around the larger particles. I ran my thumb across it. Like Braille, or an oyster forming its pearl. I handed the photo back and asked their names. He was older than me, by a couple of years. I couldn’t think of anyone with whom I had been friends back then who hadn’t been my own age. I knew only one married couple, newlyweds—they’d done it on a dare—and was friends with no parents.

What was I up to these days, he wondered, putting away his wallet. I told him about my career in film (here I introduced Sri Lanka and the editor), leaving out mention of my moonlight occupation at the movie theater. I offered an anecdote about production and its misadventures: the night of the Winnebago stunt. The punch line had me picking the short straw and suck-siphoning gasoline from a grip truck because New Jersey gas stations close early on Sundays. Who knew! It was a well-honed bit, one that usually had people in stitches and got that glow of envy going in their eyes. But my friend here was curiously unimpressed. Not that he didn’t listen politely and chuckle on cue, but there was something in the quality of his listening that made my own words sound in my ears like a child trying to impress the family dinner guest. He told me it all seemed very exciting, and although his tone wasn’t exactly condescending, it was clear that he was saying this only because he could sense I wanted to hear it.

I turned the subject back his way, in part as a stall tactic—Sri Lanka and the editor were making noises about the stairs, and I had no desire for the lunchtime conversation these fourteen flights would lead us to—but also because the new mystery of who this man was exactly had taken root. He told me he was teaching, or rather would be teaching as soon as the new semester began, at the university uptown. He went on to explain in an offhand way, almost dismissively, that he’d written a book.

Sri Lanka broke in, looking at our guest for the first time. “So what’s up with the elevators?”

“The right one’s out of order,” he said. As if to corroborate, the alarm began clanging.

The editor walked over to the stairway exit. Sri Lanka followed and on the threshold shot me a look that said, Now.

I apologized and shook the man’s hand again. I wished him luck, a wish he returned with an ironic smile. Was it really so obvious?

On the jog down, Sri Lanka aborted our mission. The timing was all off, he whispered, and so was the power dynamic. We would have to wait until next week to fire the editor. I didn’t get it but whispered back that I agreed wholeheartedly. We called it a day after lunch at a deli with upscale steam tables and plastic-utensil seating, which left me with some time to kill before my shift.

At Tower Records I gave over a solid hour to the various listening stations. Under the greasy clamp of those headphones, eyes closed, I tried to lose myself to the music. Instead, I pictured my long-lost friend’s odd face. It was familiar. But from where? With thirty minutes to spare before my shift, I stopped in at Shakespeare Books.

He’d mentioned the title in the course of our chat, and at lunch I scribbled it down on a napkin. I approached a kid in pajama bottoms, staff tag around his neck, and handed him the napkin. I had been expecting a blank stare, but was led without hesitation to an island display in the middle of the store. Judging by the assured path he traced through the maze of shelves, this was not an uncommon request. He disappeared and left me to sort through the paperbacks on display. The sign overhead designated them as STAFF RECOMMENDED.

I found the book, partially hidden by a new translation of Borges’s Collected Fictions. Literature? I had been expecting something more, I don’t know, academic: philosophy, some proof disproving some other proof. I picked it up. It was a slim volume entitled Goldmine/Landmine. On the cover, in bold, was the name:

Arthur Morel.

My job at the theater wasn’t the worst thing in the world. There was a kind of glee to our aisle frolic around the emptied auditorium, screen blank, lights up. A perverse pleasure taking in our janitorial duty. Impatient for our rightful place on the red carpet, we ushers spent our downtime debating which actors might play parts in our unsold scripts, dateless schoolgirls planning outfits to the junior prom.

I took my fifteen in the cement break pit with a cup of root beer and a bag of popcorn, then made my way to the ticket booth with Arthur’s slim book for the rest of what I hoped would be a slow evening. From behind the bulletproof face of the theater, the booth contained an earplugged rush of silence. The flutter of money being counted, the pebble clatter of change in the pan—these were the only sounds inside. An entire marching band on parade down the street would register as a polite and twinkling spectacle—and, if you were reading a book, not even that. When the shadow of a customer would darken your page, you’d flip on the thin otherworldly chatter of the squawk box. “Two adults,” they’d say, as though they were announcing themselves to you generically, in the third person. The machine would clunk up two tickets that you’d slide through the change pan. It was a welcome isolation from the crowd control the other positions required. You relaxed into a crouch on your stool until your butt got sore, just in time for the manager to come count you out.

To my frustration, however, it was not a slow night. Everyone was here to see the new Almodóvar, which had probably just been nominated for something because until now the screen it flickered on played to a virtually empty theater. I read the dedication page four times before giving in to the demands of the throng. It would just have to wait. The late show got out at 11:17. After closing, and if I walked briskly enough, I could make it through the front door by midnight.

Home, I stripped off my tie and had a seat at the upright piano parked under my bedroom window, a mid-century Baldwin that hadn’t been tuned since before I left for college. It was a sad old horse. Its uneven keys had the look of nicotine-stained fingernails. The mahogany veneer was splintering off in places; along the side that faced the bare radiator pipe, its finish was blistering like a ripe sunburn. I switched on the small gooseneck lamp on the stand and got out Arthur’s book. According to the preliminary pages, it had appeared in h

ardcover a year prior. There was no author photo, and the About-the-Author, which I was hoping might offer a clue, was not helpful. “Arthur Morel lives in New York City with his wife and son.” On the back were several blurbs. Russell Banks and Martin Amis both effused about this debut talent. The New Yorker: “… an astonishing feat of language.” The New York Times Book Review: “… unflinching eye for difficult truths; one trembles to think where that eye will turn next.”

Astonishing. Unflinching. I formed a silent chord with my right hand, bringing each key down slowly, to the bump of the key bed.

It seemed that Arthur hadn’t changed a bit.

2

APPLAUSE

I AM FIFTEEN—FOR A CHILD PRODIGY, something of a late bloomer. It’s Saturday. I am standing on the platform at Christopher Street Station waiting for the Uptown local. This is the age of the brass token, before the hipster renaissance in Brooklyn and Queens, before If You See Something Say Something. You might encounter any number of things on the platform in those days. This morning: a blood-soaked sock and a paper cup filled with quarters, on the cup’s side scrawled TAKE ONE I DAIR YOU. As I wait for the train, I try to imagine the scenario in which these two props intersected. The head and rear cars are usually empty at this hour, and I have been warned against boarding either. Safety in numbers, which will be made pointedly clear later that same year when a kid not that much older than myself will enter and sit down beside me in a cleared-out car. He will put a knife to my groin and demand twenty dollars, and after I hand him a wallet with only a few singles in it, he will punch me in the face and take off at the next stop through the ding-dong closing doors.

I board somewhere toward the middle and find a seat. Between my knees, my cello in its pleather case, on my lap my pleather valise. It is a forty-five-minute ride, time enough for music-theory homework—coordinating bouts of scribbling to the periodic moment of stillness at a station. Each stop accumulates and rotates out passengers, and once we pass 86th Street it’s mostly us, instrument cases between our legs, working out difficult fingerings on an arm or a knee. A curious look from a paint-splattered construction worker, from a Hispanic mother with a bag of groceries. The subways shriek and buck, dying with a shudder between stations. Sitting in the dark is like floating, the scraping squeal of a passing train a flicker of blue sparks against the scratched windows. Then it wakes and drags itself along to the next stop.

The Morels

The Morels